Michael S. Moynihan (Excerpted with permission from The Heights website. The original article can be found here.)

In our times, entertainments of choice, especially for school age children and young adults, are primarily electronic: video games, television, movies, music, and certain aspects of the Internet – what we are calling the entertainment culture. And while the rowdy citizens of ancient Rome left the Coliseum to return to their often drab existence, these modern forms of entertainment follow us right into the heart of our homes and indeed, with the proliferation of sophisticated mobile communication devices, almost wherever we go. That the intensity and prevalence of these modern forms of entertainment pose challenges for education is well known by those in the profession. Young teachers at the all boys school at which I teach assure me that…many male college students are choosing video games over not only their studies, but even over interest in young women.

In our times, entertainments of choice, especially for school age children and young adults, are primarily electronic: video games, television, movies, music, and certain aspects of the Internet – what we are calling the entertainment culture. And while the rowdy citizens of ancient Rome left the Coliseum to return to their often drab existence, these modern forms of entertainment follow us right into the heart of our homes and indeed, with the proliferation of sophisticated mobile communication devices, almost wherever we go. That the intensity and prevalence of these modern forms of entertainment pose challenges for education is well known by those in the profession. Young teachers at the all boys school at which I teach assure me that…many male college students are choosing video games over not only their studies, but even over interest in young women.

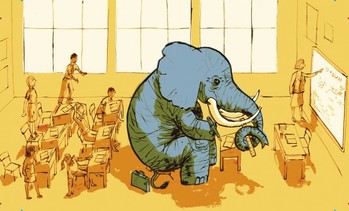

It is interesting to think a bit more deeply about the educational problems posed by living in an entertainment culture. It is not just a problem because of the amount of time wasted, time spent in front of various screens. Television and, we can add, the rest of the entertainment culture, can be quite destructive, rotting interior senses, destroying imagination, cluttering the mind, and dulling and weakening the intellect. To understand this better it is helpful to reflect on the activity referred to as “studying.” Studying is a type of human work aimed at gaining knowledge and understanding that requires disciplined use of the mind over a period of time. That studying necessarily requires a sustained effort is clear when we consider some examples of studying: engaging a great work of literature, learning about a complex biological system (such as respiration), or understanding the intricacies of a certain historical period. The fortitude to maintain one’s concentration and focus is necessary, not only to avoid quitting, on the one hand, by either simply giving up or by wasting time through daydreaming, but also to keep on task, to resist giving into curiosity so as not to be led away from the task at hand on a tangent. A classical understanding of this process highlights the active role of the person’s interior faculties in studying: the necessity of one’s imagination producing the images that the intellect uses to understand and analyze. The images generated by one’s imagination and presented to the intellect have been called, in certain philosophical schools, the phantasm. The intellect with its rational powers acts upon the phantasm. Reading requires that the mind work to transform the written word to something that one can ponder. In study and reading it is the interior intellectual faculties (imagination and intellect) that are necessarily operating in an independent, self-directed, and active manner.

The entire mental state changes when someone receives images from a screen. Rather than consciously directing its attention and producing the images necessary for thought by itself, the mind is semi-hypnotized – it lazily absorbs and follows the images that are presented to it on the screen.

Whereas normally the imagination must work to produce the phantasm, an audiovisual image, for the most part, supplies the phantasm to the person absorbed in watching it. Even if the mind does filter and modify the film images in some way this is slight and done in a passive manner rather than actively by the person. It is a common experience for someone’s own image of a literary character or scene in a novel to be changed once a movie version has been viewed. Though the imagination can still function to some extent when watching a video, especially if the video is displaying material at a slower, more human pace, the very nature of the medium requires some surrender of control over the thought process. This surrender becomes more pronounced when the video images are intense, fast-paced, and engineered with sounds so as to engage the emotions as well. In such cases, though the reasoning powers of the intellect are not directly violated (it is not as if the screen image forces the intellect to reason in a certain way), the intellect is manipulated by not being allowed the time to reflect in accord with its normal pace of operating. The attention span shrinks. There is no time to ponder the images.

On the other hand, a film that is slow-paced, full of long scenes with significant and sophisticated dialogue, is received in a manner much closer to that of reading a book, a manner much more in accord with a normal human mode of operation. The mind has time to consider the information presented to it and, though the images do certainly have an impact on the imagination, the person is left freer to ponder what he or she is receiving. Many such films can be of benefit to the humanity of those who watch and reflect on them.

At the extreme other end of the spectrum are video games and, even further, pornography. In the virtual world of video games the person not only is engrossed and swept away by the images and sounds, but he even becomes an actor of sorts in this virtual world.

Regardless of whether we are considering the audiovisual images of television and film or video games, the person who indulges in the entertainment culture not only suffers some destruction of his humanity, some loss of his personal integrity, but his relationship with reality also suffers. Entertainment overload dulls the proper sense of intellectual wonder that should exist whenever anyone devotes his efforts to learning about reality. Contact with reality has been replaced with captivation by “virtual reality.” And in the process, perceptions of the real world change. Modern man looks at reality and is too often bored; what should invoke wonder is seen as dull. The beauty of nature, a tree or a sunset, is a subtle beauty, a beauty that must be seen with a contemplative eye to be appreciated. There is a human pace to friendship, to appreciating another person for who he or she is and can be. Someone who lives at the pace of a video game, who is engulfed in “entertainment driven virtual reality,” has a much more difficult time developing strong friendships.

Toward a solution: A call for a new asceticism and the recovery of silence

Part of the solution becomes apparent from the diagnosis of the problem: if the most significant reason behind the current crisis in education is over stimulation from indulgence in entertainment, then it is clear that the entertainment (or most of it) must go. Though this renunciation will be difficult, I do think that very little progress in addressing the current crisis in education can occur until this generation becomes “unplugged.” What is needed is a broad cultural awakening to the need for a new asceticism which makes room for the cultivation of silence.

Part of the solution becomes apparent from the diagnosis of the problem: if the most significant reason behind the current crisis in education is over stimulation from indulgence in entertainment, then it is clear that the entertainment (or most of it) must go. Though this renunciation will be difficult, I do think that very little progress in addressing the current crisis in education can occur until this generation becomes “unplugged.” What is needed is a broad cultural awakening to the need for a new asceticism which makes room for the cultivation of silence.

It is essential for a vibrant intellectual life that a person focuses on a text in silence. This silence is not just the absence of noise. It is the strenuous silence of one who has the studious fortitude to engage a difficult text, to memorize what needs to be memorized, to analyze, and finally to contemplate. The key here is building up virtue, understood particularly as the fortitude to persevere in the difficult task of study and the temperance to ponder matters throughout the day. This will require ascetical struggle: the effort to forgo distracting entertainment to preserve the silence necessary to really learn.

A good teacher, someone who knows that part of his role must be as an academic coach dedicated to forming virtues in his students, especially fortitude and temperance, also knows that the full sense of a liberal arts education does not stop here. More than just a training of the mind, it is a liberating of the mind. Indeed, the word “liberal” comes from the Latin root word liber meaning “free.” The person is freed not only from being governed by his passions and affections but, over time, even from the opinions that he has picked up from the culture in which he lives. He can enter into a great human dialogue on matters of fundamental importance: the meaning of our common humanity, the possibility of genuine self-sacrificing love, human suffering and death, in short, all the primordial human experiences that have inspired the greatest works of art, literature, and philosophy throughout the centuries.