In Western society, music education has been valued since the beginning precisely because, as Plato wrote in the 4th century BC, it penetrates deeply into the mind and takes a most powerful hold on it, and, if education is good, brings and imparts grace and beauty, and if it is bad, the reverse (Republic, 401d). Music has also been at the heart of conversion. It was through the singing of St. A mbrose, that St. Augustine was converted to the Catholic faith: The voices flowed into mine ears, and the Truth distilled into my heart, whence the affections of my devotion overflowed, and tears ran down (Confessions, IX: 6). Sacred music, in particular, is a powerful tool for teaching the faith. St. Bede records a certain “John, archchanter of the church of the Holy Apostle Peter, and abbot of the monastery of the blessed Martin (of Tours), who was sent to teach the Catholic faith to the English people through music.” Excellent sacred music is important to Catholic education and conversion, because it naturally supports faith and reason, the two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth (John Paul II, Fides et Ratio). Catholics ought to take a good look at music, then, and specifically at music in our Catholic schools.[restrict]

mbrose, that St. Augustine was converted to the Catholic faith: The voices flowed into mine ears, and the Truth distilled into my heart, whence the affections of my devotion overflowed, and tears ran down (Confessions, IX: 6). Sacred music, in particular, is a powerful tool for teaching the faith. St. Bede records a certain “John, archchanter of the church of the Holy Apostle Peter, and abbot of the monastery of the blessed Martin (of Tours), who was sent to teach the Catholic faith to the English people through music.” Excellent sacred music is important to Catholic education and conversion, because it naturally supports faith and reason, the two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth (John Paul II, Fides et Ratio). Catholics ought to take a good look at music, then, and specifically at music in our Catholic schools.[restrict]

What makes music catholic, or universal? When literary convert and New-Englander Orestes Brownson wrote in defense of Catholic liberal education in the 1860s (against Horace Mann, John Dewey, and other advocates of Protestant, public education in Massachusetts), he identified the marks of a truly catholic education. One of them, he writes, is that our schools are obligated to teach catholic, or universal, truth. Citing the rule of St. Vincent of Lerins, quod semper, et quod ubique, Brownson argues that Catholic schools must promote things which are always and everywhere true, good, and beautiful (Brownson’s Quarterly Review for January, 1862). These things ultimately flow from, and lead us to, Christ our Creator and Redeemer, from whom all good things come. Catholic music, therefore, ought to possess an enduring, universal beauty.

Justine Ward, a well-respected music educator in the early 20th century and the founder of the Ward Method, echoed these sentiments in response to Pope Pius X’s reforms of music. [Catholic music] must reveal [the faith], even interpret it, and, through the outward manifestation of faith, raise the heart to an understanding of its inner meaning; it must, by means of the natural, help the weak human heart to rise to the heights of the supernatural. (Atlantic Monthly, April, 1906).

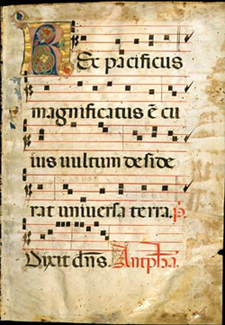

In her time, as well as in ours, no music is better suited to this purpose than plainsong or Gregorian chant. Pope Paul VI wrote, “The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy: therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 1963). As late as 2002, the United States Council of Catholic Bishops wrote, “Gregorian Chant holds pride of place because it is proper to the Roman Liturgy” (General Instruction on the Roman Missal).

Gregorian chant draws its beauty and practical strengths from three memorable characteristics: chastity, poverty, and obedience. Gregorian music is pure, chaste melody, with no underlying harmony or accompaniment necessary. As such, one person or ten thousand can perform it with ease. Gregorian music takes the vow of poverty: it uses a comfortably limited range of notes. It requires no expensive instruments or expensive copyrighted sheet music; it requires only the willing voice and a photocopier (all Gregorian music is in the public domain). Finally, Gregorian music is obedient to the sacred text. Through it, the little Catholic school child is learning to pray, not only in words, but also in song; not only in the Church’s language, Latin, but in her musical language, chant. For the purposes of music education, this plainsong or Gregorian chant is ideal.

It may also be ideal for our parishes. As the new English translation of the Mass is introduced over the coming year, much of the vernacular music of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s will become categorically obsolete, and many parishes are already turning to Gregorian music to bring stability and beauty to their Masses. Ironically, multilingual parishes have been the vanguard in this movement, because of the practical advantages of Latin music, and chant in particular. The new Cathedral of Christ the Light, Oakland, California, is a good example. At the bishop’s request, Dr. Rudy de Vos introduced chant as the ordinary for the Masses in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese, with great success and acclaim.

Furthermore, Gregorian chant is the foundation for most subsequent Western music, just as Latin is the basis of most Western languages and the human voice is the basis for most melodic instruments. Palestrina and J.S. Bach used chant melodies as the cantus firmus in most of their compositions. Mozart and Beethoven incorporated chant in their symphonies. Schumann alluded to an Ave Maria in a lieder he composed as a wedding gift for his wife, Clara Wieck Schumann. The Dies Irae chant is a recurring motif in several works by Berlioz and Wagner. Messiaen, Reger, Faure, Durufle, and even Orff returned to the chant extensively in the 20th century. Many of the best-loved works of these composers have melodies stolen from the chant. Even Appalachian folk tunes trace their origins to chant modes and melodies. Understanding the chant renders all other music much more intelligible. It allows one to understand music from the inside out.

Catholic schools, therefore, ought to put a great value on high-quality music education, with a specific focus on teaching children to sing beautifully for Mass. Headmasters ought to seek out qualified teachers with specific expertise and training in healthy vocal technique and plainchant. Before mastering polyphonic anthems, hymnody, or instrumental music, every child ought to know how to sing the simple Gregorian setting of the Mass ordinaries (Kyrie, Gloria, etc) and other basic music of the liturgy.

Many resources are available for learning to sing plainchant. Without question, the best guide to reading and singing chant is Plainchant for Everyone by Mary Berry, published by the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM). New copies are available through any online bookseller. In less than fifty pages, Dr. Berry explains the chant in simple terms which make even the most difficult music accessible. Her approach to chant is noble, simple, authentic, and free of the peculiarities which predominate in other interpretations and make the music unnecessarily difficult.

Online, numerous free resources are available from the Church Music Association of America (CMAA) at http://www.musicasacra.com/communio. The sheer number of online books and .pdf files available here may be daunting, so let me recommend a few: The Parish Book of Chant, the Liber Usualis (visit the “Guide to Interpretation” beginning on page 17 in the .pdf), and the Gregorian Missal (containing side-by-side translations). The Liber Usualis is organized exactly like a hand-missal, only the proper texts for feasts and Sundays are set to music.

In the end, however, the best resource for learning plainchant is a knowledgeable person. Like many of our Church traditions, plainchant is a living tradition. If no one is experienced with plainchant in your parish, try listening to Mass on EWTN while following the music in the Gregorian Missal. If you have trouble learning a certain chant, search for that chant on youtube.com. If you are willing to travel, come to the annual summertime CMAA Sacred Music “Colloquium” in Pittsburgh, PA. For minimal cost, a week of classes is offered in all areas of Sacred Music, for musicians at all levels of experience. The CMAA also occasionally offers sessions in local parishes.

What then, can a Catholic educator do to begin teaching this music? The answer is simple: begin singing it! Learn one bit at a time, and then teach it! Begin with a simple Agnus Dei and proceed to the other ordinaries (Sanctus, Gloria, and Kyrie). Next tackle a simple setting of the Nicene Creed, such as Credo III. Add a Communion verse and gradually add the Introit, Offertory, Alleluia, and then Gradual. Build challenges on successes. Take the time to sing beautifully, and teach the children to pray when they sing. Perhaps then, when our children have restored beauty to our churches, we will echo the words of the Psalmist: I was glad when they said unto me, “Let us go into the house of the Lord.”

Joel Morehouse teaches music and history at the St. John Bosco Schools (K-8) in Fairport, NY. He also serves as a music director and organist at St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Rochester, NY.[/restrict]